Mario and I were getting on a plane the other day, in our typical Italian-Teutonic fashion. He ambled up into line before our group was called. I waited farther back. He motioned me to come forward. I didn’t want to “cut” in front of the people I was behind.

Mario strode down the walkway ahead of me, while I, somewhat disheveled, juggled a cellphone I’d just hung up, my purse and a bag. A man nearby, having observed our interaction, said to me, “You guys look like you’ve been together a long time.”

The comment made me smile. In a way, it was true. I’ve been in relationship with Mario longer now than I was with Phillip, long enough for us to develop a couple culture, which is a kind of shorthand that develops over time between two people.

I think, without stating it in so many words, the loss of couple culture is one of the things we mourn deeply when we lose a love, whether by death, divorce, or some other separation. And no wonder we mourn losing it. That person, with whom we feel seen and acknowledged and connected, suddenly is not there.

Couple culture is a state of understanding and being understood; you don’t have to explain everything in every conversation from scratch. A lot of times, it’s a basis for play and how you relate to each other in your own private sandbox.

It’s also probably fair to say that “bad” couple cultures are at the root of a lot of divorces. (“He always does THIS.” “She always does THAT.”) But “good” couple cultures help solidify relationships. You create a common language of mind, body and spirit with all the complexity and nuance that implies.

So this gig I’ve been doing lately that had Mario and I boarding a plane together (sort of) requires me to record sound snapshots of things like restaurant service. When Mario and I aren’t interacting with staff, the recorder continues, and our personal conversations invariably wind up on the tape, too. Couple culture. In your face.

I am what Mario (and a lot of other people) call bossy. I come from a family of bossy women. I’m a know-it-all, whether I really “know” something or not. Mario, on the other hand, is a force of nature. I like to call him a big tree because his is a formidable presence. Safe to say, whatever I dish out, he can take. Or put up with. There are no withering violets in this match-up.

This exchange occurred after a server brought us some cracked, fresh coconut. Imagine comedian Dane Cook doing this dialogue. That’s what it sounded like.

I should also point out that Mario runs circles around me intellectually. He is a renaissance man, educated by Jesuits, who has poked his nose into more books on more subjects than I will ever hope to. It’s just that, I’ve read more books on nutrition.

The other thing is: We’re not angry in this exchange. We’re having fun, playing a little relationship ping-pong.

Anyway, here goes:

Mario: Coconut is good for you!

Ann: No, it’s not.

M: Wuh?

A: It’s got saturated fat in it.

M: It’s water soluble.

A: No, it’s not.

M: How can something that grows on a tree be bad for you?

A: Well…. Is there fat in avocado?

M: Um-hum.

A: There’s fat in coconut.

M: It’s water soluble.

A: Fat is not water soluble.

M: Yes, it is. The fat in avocado is water soluble.

A: It’s completely impossible.

M: Are you sure?

A: Yeah. Fats are fat-soluble. Water-soluble things are water-soluble. Fat can’t be water-soluble.

M: Well, why do “they” always say that the fat in avocado is water-soluble?

A: “They” never say that.

M: I’ve heard it said a million times.

A: You have not.

M: Yes, I have.

A: Avocado is not water-soluble.

M: The fat in avocado is water-soluble.

A: No, it’s not.

M: That’s what I’ve been told.

A: I don’t know where you heard that.

M: You better check it out.

A: It’s wrong.

M: You may think it’s wrong. But you may not be right.

A: On this one, I am right.

M: You may think on this one, you’re right. But you may not be. You may not be right.

A: But I am right.

M: You don’t know that.

A: But I do, without a doubt. Without a question of a doubt. If you don’t think so, make a wager.

M: Are you ready to go?

Talk about savoring every morsel. Later that night at an Italian dinner, Mario baits me with the statement that the fat in olive oil is water soluble. He's got a twinkle in his eye. I snap at the bait, we laugh, and our journey of parallel souls continues.

Once again I drove to the car wash today. Once more to have the mud and grime cleansed from the surface of this car, which was Gregory’s car before it was my car. I’m sure people look at me sideways as I pull in; the little Celica surely looks battered for its 13 years, like a car most people wouldn’t bother to clean.

Once again I drove to the car wash today. Once more to have the mud and grime cleansed from the surface of this car, which was Gregory’s car before it was my car. I’m sure people look at me sideways as I pull in; the little Celica surely looks battered for its 13 years, like a car most people wouldn’t bother to clean.

This is not something that should have happened to Gregory’s car, which he bought new in 1993. For the first five years of its life, the Celica was washed twice a week by hand. If you sat down in the passenger’s seat and perchance a leaf had attached itself to your shoe, Gregory would lean over and pull the detritus off the spotless mats. The Celica was garaged at home as well as at work, contributing further to the riddle of the cancer.

This is not something that should have happened to Gregory’s car, which he bought new in 1993. For the first five years of its life, the Celica was washed twice a week by hand. If you sat down in the passenger’s seat and perchance a leaf had attached itself to your shoe, Gregory would lean over and pull the detritus off the spotless mats. The Celica was garaged at home as well as at work, contributing further to the riddle of the cancer. When we met, Gregory was years past his last encounter with a doctor. He’d had some dental work that had become infected, which he was careful to have treated. And much earlier, he had been shot and nearly died. That’s another story, but it was shocking the first time we made love to see a rough scar running from front to back around the bottom of his left rib-cage. He’d been shot during a robbery and had bled, and when the docs cut into him, niceties like appearance were not on their minds. They were more concerned with saving his life. Which they did.

When we met, Gregory was years past his last encounter with a doctor. He’d had some dental work that had become infected, which he was careful to have treated. And much earlier, he had been shot and nearly died. That’s another story, but it was shocking the first time we made love to see a rough scar running from front to back around the bottom of his left rib-cage. He’d been shot during a robbery and had bled, and when the docs cut into him, niceties like appearance were not on their minds. They were more concerned with saving his life. Which they did. During one episode, his wife told me later, he had been standing next to the hood of their car and grabbed his chest and crumpled to his knees. He told her that for a moment he thought he was going to die.

During one episode, his wife told me later, he had been standing next to the hood of their car and grabbed his chest and crumpled to his knees. He told her that for a moment he thought he was going to die. In the ensuing years since Gregory’s death, I have loved the Celica. Loved the feel. Loved the design. Loved its looks. Loved the fit. Even loved its cranky, unforgiving clutch. But out of nowhere, despite babying, despite keeping it out of the sun far more than letting it sit in the sun, despite coddling it like the creampuff it’s been, the cancer came creeping. The flaw began to show itself.

In the ensuing years since Gregory’s death, I have loved the Celica. Loved the feel. Loved the design. Loved its looks. Loved the fit. Even loved its cranky, unforgiving clutch. But out of nowhere, despite babying, despite keeping it out of the sun far more than letting it sit in the sun, despite coddling it like the creampuff it’s been, the cancer came creeping. The flaw began to show itself.

Or maybe just a simple recycled bag, from say, In-N-Out?

Or maybe just a simple recycled bag, from say, In-N-Out?

Mario keeps prodding me to talk more about our respective mates and food. After all, the title of this blog is, “Table for Four, Dinner for Two.” And there are many food moments still to share. For, indeed, while eating and dining and gathering 'round a table are central to everyone’s lives, they are the heart and soul of existence for foodies like us.

Mario keeps prodding me to talk more about our respective mates and food. After all, the title of this blog is, “Table for Four, Dinner for Two.” And there are many food moments still to share. For, indeed, while eating and dining and gathering 'round a table are central to everyone’s lives, they are the heart and soul of existence for foodies like us.

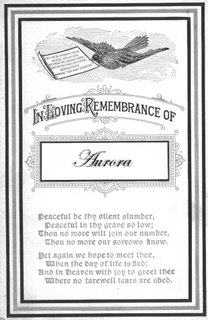

Mario was able to take Izzy’s ashes to Assisi in Italy. I had wanted, along with Gregory’s cousins, to spread Gregory’s ashes at places that were important to him. In my case, it was an accomplishment just to get Gregory cremated. Aurora was Catholic. She had a family plot in a prestigious cemetery. (Yes, status can extend beyond the grave.) Although the thought of that beautiful body consumed in flames was not a pleasant one, I knew it was what Gregory would have wanted. “I don’t want to be buried,” he said, “all dressed up with no place to go.”

Mario was able to take Izzy’s ashes to Assisi in Italy. I had wanted, along with Gregory’s cousins, to spread Gregory’s ashes at places that were important to him. In my case, it was an accomplishment just to get Gregory cremated. Aurora was Catholic. She had a family plot in a prestigious cemetery. (Yes, status can extend beyond the grave.) Although the thought of that beautiful body consumed in flames was not a pleasant one, I knew it was what Gregory would have wanted. “I don’t want to be buried,” he said, “all dressed up with no place to go.”

Mario has just returned from a two-week trip to Italy – business, but hey, how bad can ANY business trip to Italy be? – and something has shifted. Instead of flooding into his space with my needs, I have felt compelled to just enjoy his company and do whatever I can to make his landing in the home time-zone soft and comfortable.

Mario has just returned from a two-week trip to Italy – business, but hey, how bad can ANY business trip to Italy be? – and something has shifted. Instead of flooding into his space with my needs, I have felt compelled to just enjoy his company and do whatever I can to make his landing in the home time-zone soft and comfortable. Each of their children spoke movingly of their father and mother. Violet read a piece that she had written about him, her voice faltering toward the end.

Each of their children spoke movingly of their father and mother. Violet read a piece that she had written about him, her voice faltering toward the end.

I’ll tell you right up front: Mario has counseled against writing what I am about to write.

I’ll tell you right up front: Mario has counseled against writing what I am about to write.

But it was true. This indeed was Gregory. And I could feel sweet, protective shock again licking at the edges of my mind.

But it was true. This indeed was Gregory. And I could feel sweet, protective shock again licking at the edges of my mind.